An interesting example is #"H"-"C"-="C"-"H"#, acetylene.

We utilize the convention that the #z# axis points along the internuclear axis. Since the #p# orbital that overlaps head-on with the #s# orbital is along the internuclear axis, the #2p_z# orbital of carbon will the one that is compatible with the #1s# of hydrogen AND the #2s# of carbon.

)

)

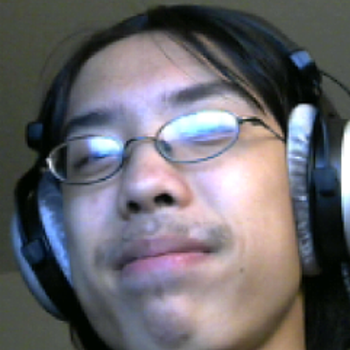

The two carbons each have #\mathbf(sp)# hybridization, where they mix their #2s# and #2p_z# orbitals together, achieving an #\mathbf(sp)# hybrid orbital of #50%# #s# character and #50%# #p# character, with a new, lower energy, between those of the two original atomic orbitals. This can overlap with hydrogen's #1s# orbital.

That accounts for each ** #\mathbf(sigma)# bond that each carbon makes with the other carbon and one of the hydrogens; see (a)**.

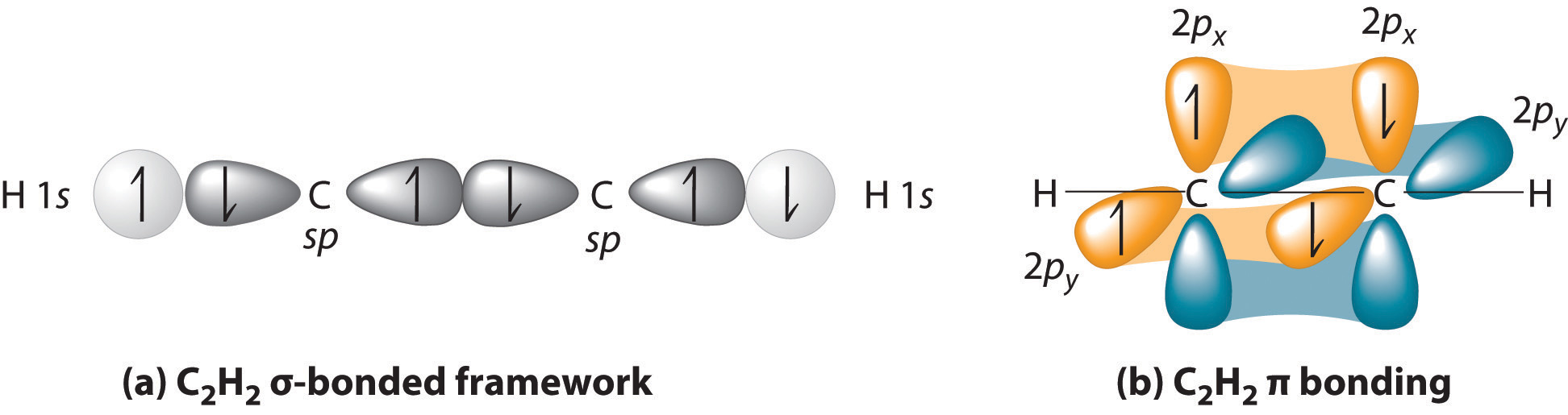

Then, the remaining #2p_x# and #2p_y# orbitals of each carbon can respectively overlap with the #2p_x# and #2p_y# orbitals of the other carbon (i.e. #2p_y# with #2p_y#). These CANNOT overlap with hydrogen's #1s# orbital.

These account for the two #\mathbf(pi)# bonds; see (b).

Overall, we get that each carbon uses two #sp# hybrid orbitals by mixing the #2s + 2p_z# orbitals in order to overlap with hydrogen's #1s# orbital and form a #\mathbf(sigma)# bond with one of the hydrogens and the other carbon, and each carbon uses its #2p_x# and #2p_y# orbitals to generate two #\mathbf(pi)# bonds with the other carbon.

The two #\mathbf(pi)# bonds and one #\mathbf(sigma)# bond made by each carbon with the other carbon accounts for the triple bond.

)

)